All design and meaning, without exception, is some kind of replicating physical pattern upon which entropy acts in the form of natural selection.

“The Darwinian Acid” is a phrase that comes from Daniel Dennett’s breathtaking book, Darwin’s Dangerous Idea: Evolution and the Meanings of Life. As I mentioned in the previous section, Dennett is a naturalist who combines the Galilean and Darwinian worldviews in opposition to that of Paley and his positions regarding Darwin’s theory of natural selection as uncompromising as they come. (Darwin did not invent evolution – something we will address more in the next section – but the mechanism responsible for it.) While it might seem extreme though it might seem to many readers, I will take Dennett’s rigid perspective on natural selection as a starting point for the Darwinian argument I would like to build. The upside of this is that if I can provide an argument that pushes back against Dennett’s Darwinism, it is very likely that the same argument will also work against other, less dangerous versions of that idea.

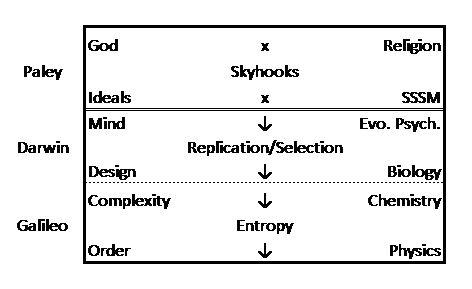

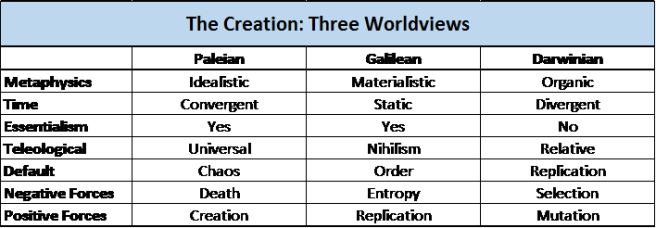

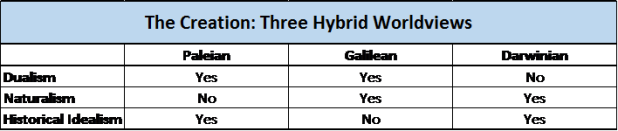

Being the committed naturalist that he is, it is worth pointing out the tensions and contradictions that we can expect Dennett’s account to both address and contain. The primary motivation of the book is a desire to banish all ideals that we might be tempted to smuggle in from the Paliean worldview. According to Dennett, all purposes and meanings that actually exist, in the broadest sense and without exception, must be determined by and follow from the nature of the physical world rather than the other way around. All purpose and meaning therefore must have evolved from within the organic worldview of Darwin, which in turn must have emerged from the physical worldview of Galileo. Any dualistic or idealistic suggestions that some mind or purpose might determine, constrain or stand outside of the natural world are dismissed as miraculous and superstitious skyhooks. Thus, he is especially concerned with undermining all non-naturalistic Darwinians – the historical idealists – whose ideals are no less skyhooks than those of the dualistic creationists. It is for this reason that Dennett is sometimes called a “Darwinian Fundamentalist.”

While it may be tempting to see Dennett’s uncompromising naturalism as unnecessary and extreme, he thinks this position is actually that of standard, everyday natural science as it is taught and practiced within every university. Thus, he think that one cannot call his position extreme without also calling well-supported science extreme as well:

“My project, then, is to demonstrate how a standard, normal respect for science – Time magazine standard, nothing more doctrinaire – leads inexorably to my views about consciousness, intentionality, free will, and so forth. I view science not as an unquestionable foundation, but simply as a natural ally of my philosophical claims that most philosophers and scientists would be reluctant to oppose. My ‘scientism’ comes in the form of a package deal: you think you can have your everyday science and reject my ‘behaviorism’ as too radical? Think again.” (Bo Dahlbom, 1995, p. 205)

For the most part, then, Dennett does not indulge in metaphysical hairsplitting and other such practices that most of his philosophically trained critics are typically inclined toward. Rather, he takes the standard tenets of the natural sciences as his premises and argues from this starting point. The strength of this strategy lies in the cultural aversion that most intellectuals feel to contradicting well-established science – especially from an armchair. The weakness of Dennett’s approach is that we have good reason to be suspicious of granting the practices of natural scientists this kind of influence over the purposes and meanings in our lives – for these are exactly the targets of Dennett’s arguments.

The other topic that Dennett wishes to confront (this confrontation is actually the very centerpiece of his entire career) is the unresolved tension within naturalism itself regarding the emergence of the purposes and meanings native to the Darwinian worldview from the nihilistic, brute causation of the Galilean worldview. On the one hand, this issue seems to be subordinate to the first, in that showing how purpose emerged from causation is itself intended to demonstrate that we have no need for any Paleian ideals from above. On the other hand, there are unfortunate times when he reverses the priority of these tensions by suggesting that purpose and meaning must have emerged from mere matter in motion since the only alternatives are Paleian ideals that, he thinks, “beg the question”:

“Whether we can imagine a non-mechanistic but also non-question-begging principle for explaining design in the biological world is doubtful; it is tempting to see the commitment to non-question-begging accounts here as tantamount to a commitment to mechanistic materialism, but the priority of these commitments is clear… One argues: Darwin’s materialistic theory may not be the only non-question-begging theory of these matters, but it is one such theory, and the only one we have found, which is quite a good reason for espousing materialism. [Dennett 1975, pp. 171-72.]” (Dennett, 1996, p. 153)

While I am willing to accept Dennett’s uncompromising naturalism as a starting point, I am not willing to embrace a principled dismissal of all Paleian ideals simply because they are not naturalistic explanations.

Replication as the Bridge to Teleology

Unfortunately, one of the places in his book where Dennett attempts to support his own position with a distracting argument against the Paleian alternative is in his discussion surrounding the emergence of Darwinian design from Galilean order. This, it is worth repeating, is the exact place where we would expect to find unresolved tensions within a naturalistic worldview. How does mere matter in motion (‘order’ we might call it) come to have a designed purpose unless somebody organizes it according to what they have in mind? More basic, what is the difference between order and design?

“What is the difference between Order and Design? As a first stab, we might say that Order is mere regularity, mere pattern; Design is Aristotle’s telos, an exploitation of Order for a purpose.” (Dennett, 1996, p. 64)

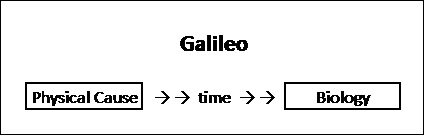

I will use this somewhat opaque statement as a springboard by describing the difference between order and design in terms of the direction of causation. Order is physical matter whose structure or behavior is mechanistically determined by what came before it as everything must be within a Galilean worldview. What happens after a physical event or process has no bearing on the event itself since physical causation does not and cannot go backwards in time. As shown in Figure 1 below, Galilean causation is a one way street with traffic flowing from the past toward the future.

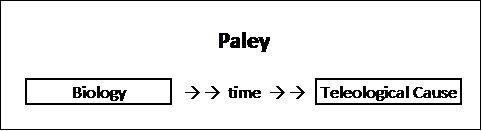

Design, by contrast, is some pattern whose structure or behavior is, in some sense, determined by what is supposed to happen in the future. As Dennett put it, design is order that is aimed at some purpose that is supposed to come later, if at all. Such purposes are right at home within the Paleian worldview where minds do and organize things for some anticipated purpose. For example, in the same way that I build a fire so that I would not get cold later on in the night, a giraffe is born with a long neck in order to eat the higher leaves off of trees when it is older. In each case of design, the future effect or purpose of the design somehow explains the prior structure and behavior of the design itself as shown in Figure 2 below.

Since a naturalist places a Darwinian worldview within that of Galileo, he is committed to the design of the former following from or being determined by the causation of the latter. Thus, not all physical order will or even can be teleological in nature, but there will be no teleological design that is not also physical in nature. The question that Dennett must answer, then, is how we can get the future oriented design of Darwin without violating the backwards looking causation of Galileo? Darwin’s mechanism of natural selection, Dennett thinks, provides the answer to this question:

“Darwin suggests a division [between order and design]: Give me Order, he says, and time, and I will give you Design. Let me start with regularity – the mere purposeless, mindless, pointless regularity of physics – and I will show you a process that eventually will yield products that exhibit not just regularity but purposive design… Darwin had reduced teleology to nonteleology, Design to Order.” (Dennett, 1996, p. 65)

And

“Darwin explains a world of final causes and teleological laws with a principle that is, to be sure, mechanistic but—more fundamentally—utterly independent of “meaning” or “purpose”. (Dennett, 1996, p. 153)

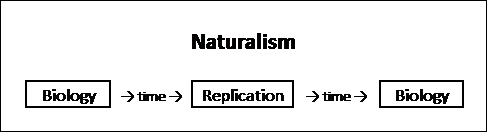

While it may be true that natural selection provides the answer to our question, it is still not entirely clear what, exactly, that answer is. What is it specifically about the process of natural selection that allows certain kinds of physical order to somehow become biological design? The answer, I suggest, is replication. Replication within a stable environment creates a situation in which generations of a particular type of biological design stretch across both space and time such that the future and past for that type come to overlap with each other. As depicted in Figure 3 below, the process of replication creates a situation in which the same event is both the past and the future cause of the design.

Teleological design thus emerges when and only when a physical pattern differentially replicates itself within a stable environment. In such cases, the physical environment mechanistically causes a physical pattern to replicate itself such that the future copies are, by definition, themselves built or designed for replicating within that same physical environment. While each individual organism is itself fully determined by physical causation, the biological species as collective type comes to be designed for the purpose of replicating itself within a stable environment. Conversely, if there is no replication, then there are no generations that extend over time, which means that the physical causation from the past will not overlap with the teleological causation from the future, which in turn means that Darwinian design will not emerge from Galilean order. Replication is thus a logical precondition for design and purpose within a naturalistic universe.

With regards to how and where replication first began on this planet, precious little is known. Both Darwin and Dennett are therefore forced to take the existence of replicating organisms for granted. Dennett thinks they can both get away with taking replication for granted because only the most radical and outlying participants in the natural sciences would object to this presupposition. Unfortunately, by papering over the historical emergence of purpose from mere matter in motion Dennett draws attention away from a point which is absolutely crucial to the consistency of the naturalistic worldview. Why, for example, should we not believe that these moderate natural scientists who accept the existence of replicating organisms are tacitly accepting a type of causation that does not, in fact, reduce to physical causation? In the second chapter I will return to this still unresolved issue, but for the time being and for the sake of exposition I will tentatively follow Dennett in accepting that existing biological organisms are indeed replicating matter in motion.

Natural Selection as Entropy

Within the Galilean worldview, the ubiquitous effects of entropy entail that disorganization is the default toward which all matter within the naturalistic universe tends. As this claim applies to a Darwinian subset of biological organisms within that Galilean worldview, the default standard for such organisms is death, or simply not living, against which all reproductive life is an exception that must be explained. To be sure, naturalism does not preclude the temporary gains against the force of entropy, within relatively small localities. In other words, Darwinian life is not impossible within a Galilean world, but it must be a temporary exception rather than the general rule. With this in mind, Dennett strongly endorses the psychologist Richard Gregory’s claim that “life is a systematic reversal of Entropy.” (Gregoy, 1981, p. 136) This systematic reversal of entropy cannot come for free within a naturalistic world. Physical work of a rather stable and well organized kind must be done in order for a biological pattern to both come into existence as well as survive for any significant amount of time. This organized work is, we have seen, purposeful, replicating design.

If the first key to understanding the relationship between physical causation and biological purpose lies in the equation of biological organisms with replicating physical matter, then the second key is the equation of selective forces with the physical process of entropy. Natural selection is nothing more than entropy acting upon physical patterns such that they fail to replicate and survive. Thus, the selective force of entropy channeling and honing the process of replication is simply the negative image of differential replication of those physical patterns. Evolution by natural selection, then, is the idea that over large stretches of space and time the process of replication channels isolated pockets of physical matter into replicating patterns of purposeful motion that were, by definition, able to perform the work necessary to temporarily resist the disorganizing tendency of entropy.

Replication is not only the bridge from order to design, but is also the physical work of a rather stable and well organized kind that must be done by biological patterns in order to both come into existence as well as temporarily reverse the force of entropy. Biological designs and purposes that struggle for survival and replication under the Darwinian view just are the stable and well-organized work necessary for physical patterns to replicate themselves in the face of relentless entropy. From a Galielean perspective, some well-organized physical patterns of physical matter are able to channel matter and energy from their environment into the construction of another well-organized pattern of physical matter that is similarly structured to channel matter and energy from that same environment to the same end. From a Darwinian perspective, biological organisms are designed for the purpose of taking resources from their environment and producing offspring. These two perspectives, according to Dennett, are both equally true in that the teleological entities (designs, purposes, resources and offspring) of the latter are not merely convenient or instrumental labels for the patterns of physical matter in motion within the former. On the contrary, the patterns of physical matter in motion within the former just are the teleological entities of the latter. In other words, teleology does not merely seem to exist from some perspective but, due to the process of natural selection, actually does exist as real patterns in the naturalistic world.

The Universal Scope of Natural Selection

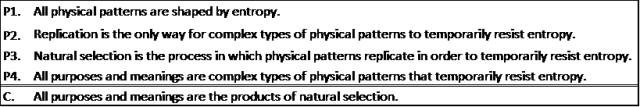

Dennett insists that the Darwinian world of teleology and design exists fully within the Galilean world of physical causation to the absolute exclusion of the Paleian world. From this follows the claim that all design and all meaning, at every level and without exception, are Darwinian in nature and are thus instances of physical “order exploited for the purpose” of replication. This is what Dennett means when he proclaims the unity of design space or when he calls Darwin’s idea (natural selection) a universal acid that eats through absolutely everything: There is no design or purpose outside of that produced and sustained by natural selection. We thus have Argument 1 (below): If all physical patterns are shaped by entropy, and if replication is the only way for complex types of physical patterns to temporarily resist entropy, and if natural selection is the process in which physical patterns replicate in order to temporarily resist entropy, and if all purposes and meanings are complex types of physical patterns that temporarily resist entropy, then all purposes and meanings are the product of natural selection. Natural selection alone provides a naturalistic explanation for all the purposes and meanings in life.

Both the unity of design space and the universality of natural selection within the realm of purpose and meaning is illustrated by the distinction which Dennett draws between cranes and skyhooks. Within this metaphor, depicted in Figure 4 below, gravity and the ground respectively represent entropy and the default state of disorganization/death to which it tends. All purposes and meanings are lifting mechanisms – designed patterns that perform organizing work – that exist within the Darwinian realm of replication. A crane, then, is a type of design or purpose that is built from the Galilean ground up by and in order to continue performing the organizing work of replication. It is some biological organism or any other complex type of physical pattern that is able to temporarily resist the downward pull toward disorganization by reliably performing the necessary work for its own replication.

Whereas all cranes are built form the ground-up, a skyhook, by contrast, is a type of design that comes from the top down. It is any process, other than physical replication, by which purpose or meaning is supposed perform the physical work of organizing and shaping the observable world. Unlike the rest of the naturalistic world, a skyhook is not subject to natural selection for the simple reason that a skyhook is (somehow) not subject to the force of entropy. The point of the metaphor is that all purposes and meanings that exist, lie within the Darwinian realm of natural selection are thus determined exclusively by the physical world of Galileo below and not by the ideal world of Paley above.

“Cranes can do the lifting work our imaginary skyhooks might do, and they do it in an honest, non-question-begging fashion. They are expensive, however. They have to be designed and built, from everyday parts already on hand, and they have to be located on a firm base of existing ground. Skyhooks are miraculous lifters, unsupported and insupportable. Cranes are no less excellent as lifters, and they have the decided advantage of being real.” (Dennett, 1996, p. 75)

Dennett’s naturalistic worldview that we have taken for granted in this section claims that all cranes – the entirety of design space – exist within the Darwinian realm of natural selection. This is a two-fold claim. First, all cranes were erected from the ground up, historically speaking. At no point did a Paleian skyhook drop down from above and lift or design anything, not even another crane that is itself based in the ground. Second, all cranes remain standing solely due to their continual grounding in the Galilean world below. Every designed thing that has historically risen above the ground must continue to perform the work necessary in order to remain there. Thus, even if we grant that at some point in the past a skyhook did drop down and build a crane that was not itself a skyhook, this second crane must itself be grounded in the physical world by way of replication. There is absolutely no “hovering” allowed. Natural selection is always operating upon every teleological entity that exists regardless of how it was first brought into existence.

The two-fold nature of Dennett’s claim thus brings all design, be it biological or of human artifice, within one and the same design space. Designed artifacts and meaningful speech patterns are themselves cranes within the Darwinian world of natural selection that must also resist entropy by way of replication. In this sense, there is no principled difference between biology and engineering since both fields of study make up the one, unified design space. This does not necessarily imply that blackboards and cars replicate themselves in the same way that plants and animals do. It does, however, imply that all such designed artifacts that are not themselves replicating cranes (biology), must instead have been lifted up and continue to be supported by some crane that does in fact replicate (engineering). Far from being the exception, then, it is very likely the case that most cranes within design space do not directly lift and build copies of themselves. Rather, these cranes replicate themselves indirectly such that cranes of type A only build cranes of type B, while the latter type only build the former. So long as every crane – every designed pattern in the entire world – has been built by or descended from (both in terms of our lifting metaphor as well as its literal genealogy) another crane, naturalism has not been violated. Framed this way, Dennett’s unified design space that includes both organism and artifact is very close to that of a pure Paleian worldview. Whereas Paley saw the entirely biological realm as being engineered by a divine skyhook, Dennett sees the entire realm of engineering as being evolved from biological cranes.

Dennett insists, then, that any proposed source of purpose, design or meaning that is not the product of or does not operate within the constraints of natural selection will under close scrutiny violate naturalism, beg the question or simply fail altogether. So strong his commitment to the unity of design space, that he takes several academics to task for bringing Paleian skyhooks into their thinking with attempts at placing their objects of study beyond the scope of natural selection. Jerry Fodor, Noam Chomsky, Stephen Gould, anybody who endorse the standard social science model (SSSM within Figure 4) and most of the humanities have all attempted to contain the Darwinian acid by various attempts at sidelining natural selection. All such thinkers, Dennett claims, are skyhookers that seek to transcend the natural world. Such a rejection of the Paleian worldview could not be stronger.

Natural Selection as Algorithm

Having defined natural selection as entropy acting upon replicating physical patterns, and having argued for the universal scope of natural selection, we can now better understand Dennett’s claim that natural selection is an algorithmic process. Darwin’s own summary of natural selection sets up this claim quite nicely:

“If during the long course of ages and under varying conditions of life, organic beings vary at all in the several parts of their organization, and I think this cannot be disputed; if there be, owing to the high geometric powers of increase of each species, at some age, season, or year, a severe struggle for life, and this certainly cannot be disputed; then, considering the infinite complexity of the relations of all organic beings to each other and to their conditions of existence, causing an infinite diversity in structure, constitution, and habits, to be advantageous to them, I think it would be a most extraordinary fact if no variation ever had occurred useful to each being’s own welfare, in the same way as so many variations have occurred useful to man. But if variations useful to any organic being do occur, assuredly individuals thus characterized will have the best chance of being preserved in the struggle for life; and from the strong principle of inheritance they will tend to produce offspring similarly characterized. This principle of preservation, I have called, for the sake of brevity, Natural Selection.” (Darwin, 1859, p. 127)

Natural selection can thus be construed as an algorithmic process that inevitably occurs when three conditions are present: 1) the biological reproduction that I have been called replication, 2) the struggle for survival that I have defined as replication in the face of entropy, and 3) the variations within that process of replication. Put another way, because physical patterns are under no obligation to replicate themselves perfectly, it is necessarily the case that some variations of any given pattern will temporarily resist the force of entropy by way survival and replication better than others. Given entropy and imperfect replication within a stable environment, natural selection will continually and inevitably operates on all teleological entities that have design or meaning.

The algorithmic process of natural selection, then, is much like Newton’s laws of motion in that it necessarily follows from and thus conceptually structures the domain of replication within a physical universe. The claim that some design is shaped by natural selection is no more optional and no less tautological that the claim that force is equal to the product of mass and acceleration. Natural selection is a kind of quality control on design that is always at work whether we like it or not.

“The first chapter of Genesis describes the successive waves of Creation and ends each with the refrain “and God saw that it was good.” Darwin had discovered a way to eliminate this retail application of Intelligent Quality Control; natural selection would take care of that without further intervention from God.” (Dennett, 1996, p. 67)

Given the two-fold nature of nature of Dennett’s claim, however, the situation is actually much worse than what he states above. It is not merely the case that ideals do not need to constrain or influence the process of natural selection. Rather, the forces of natural selection will continue to operate and influence all purpose and meaning, regardless of the intentions or even existence of God or any other Paleian ideal. The purpose for which something was created, will only be relevant to the extent that that thing it is able to resist the tendency of entropy by performing the work that is necessary for its replication. Since replication is a non-negotiable precondition for purpose, to the extent that the purpose of any design comes apart or deviates from its own replication, it will fall prey to entropy and thus extinct. The purposes and meanings of the naturalistic worldview, to repeat, follow from the nature of the physical world rather than the other way around.